Probably the most influential writer in my life was Ernie Pyle, the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and war correspondent for Scripps-Howard. Of course, he died at the end of World War II before my birth, but I could find his collected works of WWII newspaper columns in the Pease Elementary library when I was in grade school.

I recall reading Here Is Your War and Brave Men, but I don’t remember if the grade school library had Ernie Pyle in England and Last Chapter. After I left college, I found copies of all four in used bookstores and purchased them for my personal library, reading or re-reading each one.

Until I read Pyle, I never realized you could make a living by writing. That realization started me on the road to a journalism education, beginning my career with four Texas newspapers before moving into higher education communications. Pyle was a fine writer, as are many others who have worked in newspapers, but he had an uncommon empathy for the common man in his reporting.

That compassion, rendered into ink on newsprint, made him a favorite of both those fighting the war and those back home starved for details of their loved ones overseas. He wrote with such humility that reading him was like hearing from a lifelong friend with news of common acquaintances.

Pyle is best remembered for his Pulitzer Prize-winning column on the death of Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas, in the mountains of Italy. “Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules,” he wrote, then reported how each man from Waskow’s unit offered his respect, including one who silently held the dead captain’s hand for five minutes before gently straightening the deceased’s shirt collar and walking away and back into the war.

Another poignant account is of his stroll along Omaha Beach the day after the Longest Day. “It was a lovely day for strolling along the seashore. Men were sleeping on the sand, some of them sleeping forever.” He then described “the awful waste and destruction of war” by simply noting the debris on the beach. Pyle died like many of the men he covered, killed by machine gun fire on the Okinawan island of Ie Shima on April 18, 1945.

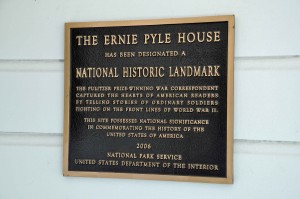

I have been fortunate to visit both his home, which is now a National Historic Landmark that serves as a branch of the Albuquerque Public Library, and his grave in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at the Punchbowl in Honolulu. I own his four WWII books as well as Home Country, a collection of the Depression-era stories he wrote about Americans during hard times. By the penciled prices on the inside of each cover, I know I paid only $6.95 for all five books. Their value to me as examples of good writing, often under deadline and length constraints, has greatly exceeded their cost.