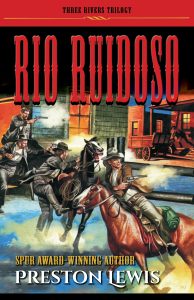

I’m pleased to post the cover for my upcoming Five Star novel Rio Ruidoso, the first book in my Three Rivers Trilogy on the Lincoln County War and Billy the Kid. The cover has a retro feel to it, like the art from the heyday of western novels.

And to anyone who is interested, I have review copies of this January release I am willing to send at no charge to anyone willing to read the book and post an Amazon review once it is published. All I ask is that you send me a request with your e-mail address so I can remind you when the book goes online and reviews can be posted. Just send me an e-mail request at pr****************@***il.com.

charge to anyone willing to read the book and post an Amazon review once it is published. All I ask is that you send me a request with your e-mail address so I can remind you when the book goes online and reviews can be posted. Just send me an e-mail request at pr****************@***il.com.

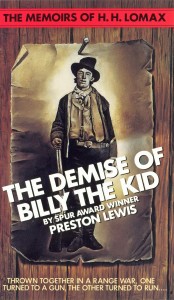

Now, I’m not the first author to write a novel on Billy the Kid. In fact, the trilogy will be the second time I’ve written a project featuring the Kid and Lincoln County War. My initial fictional foray into the Lincoln County War was The Demise of Billy the Kid, the first novel in my Memoirs of H.H. Lomax series. Demise brought me the greatest compliment of my writing career, but more on that in a moment.

While the Lincoln County War is a trail well-traveled by novelists, I’ve incorporated many of the lesser known incidents from the feud into the novels. The trilogy is named for the three Lincoln County rivers—Rio Ruidoso, Rio Bonito and Rio Hondo—that flow through the critical section of the county where much of the violence took place.

Even before the legendary feud began, Lincoln County was seething with economic, political, personal and racial vendettas. Rio Ruidoso places my protagonist Wes Bracken in Lincoln County in the months prior to the Lincoln County War when the Horrell brothers, a clan of Texas ex-patriots, started a rein of racial terror against the native New Mexicans. In Rio Bonito, the second book in the trilogy, Bracken vows against all odds to steer a neutral course between the feud’s warring factions. Rio Hondo, the trilogy’s final volume, follows my protagonist in the aftermath of the war proper when vendettas continued and the participants, Billy the Kid included, sought a way out of the deadly vortex they had created for themselves.

Billy the Kid and I go back a long way together. Though I never met him, of course, I’ve literally walked in his footsteps and feel like I’ve come to know him over the years as I have read so much about him. My fascination with him began in the 1950s when my parents took my brother and me on a trip to the mountains of Ruidoso, New Mexico. I was likely about eight at the time when Mom and Dad took us on a sidetrip to Lincoln, New Mexico. At the Lincoln County Courthouse I walked up the same stairs that the Kid had climbed during his incarceration and during his escape when he killed two deputies.

Billy the Kid and I go back a long way together. Though I never met him, of course, I’ve literally walked in his footsteps and feel like I’ve come to know him over the years as I have read so much about him. My fascination with him began in the 1950s when my parents took my brother and me on a trip to the mountains of Ruidoso, New Mexico. I was likely about eight at the time when Mom and Dad took us on a sidetrip to Lincoln, New Mexico. At the Lincoln County Courthouse I walked up the same stairs that the Kid had climbed during his incarceration and during his escape when he killed two deputies.

The most striking memory of that visit, though, was a display of a handgun from every sheriff in the history of Lincoln County. What was etched in my mind about that display was a little cardboard arrow hanging above one pistol barrel. Handwritten on the pointer were the words “Note the Notches.” Sure enough on the side of the barrel near the sight were three slight but intentional scratches. I could not believe that those tiny marks represented three lives snuffed out years earlier. The notches struck me as all the more sinister because they were so insignificant.

Some 20 years later in 1977 I took Harriet and our newborn son to Ruidoso for the first time. At the Lincoln County Courthouse I asked the docent where I could see the collection of sheriff’s weapons, including the one so vividly etched in my mind. The docent frowned and said they had been stolen from the courthouse about a decade earlier. Even though the FBI was called in to assist in the investigation, the guns were never recovered. I’ve tried throughout my life not to be a vindictive person, but I hate that son-of-a-witch for stealing that collection of guns and for depriving future children from seeing the weapon that stoked my imagination so. We returned to Lincoln last year—a pilgrimage to Lincoln being a necessity on every trip I take to Ruidoso and the mountains— and I asked the on-duty New Mexico Park Ranger if they had ever recovered the stolen weapons. She had never even heard of the guns, so I guess they are lost forever to the public.

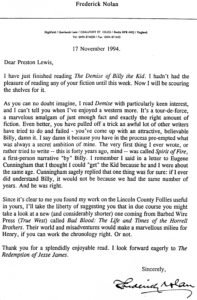

I came back from my first trip to Ruidoso fascinated by Billy the Kid and started reading as many books on him as I could, starting with Frazier Hunt’s 1956 book The Tragic Days of Billy the Kid, which I checked out of the Midland County Library. Since then I’ve read dozens of books on William H. Bonney and the Lincoln County War, including many by Frederick Nolan, a British author fascinated by the Lincoln  County War since it started with the murder of an Englishman, John Henry Tunstall. His book The Life and Death of John Henry Tunstall would be the first of a dozen books and numerous articles he published on the feud, culminating with the authoritative The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History in 1992. He is in my mind the leading scholar on the Lincoln County War, an accomplishment in itself since he lives in England and did most of his research from there augmented by occasional trips to the U.S.

County War since it started with the murder of an Englishman, John Henry Tunstall. His book The Life and Death of John Henry Tunstall would be the first of a dozen books and numerous articles he published on the feud, culminating with the authoritative The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History in 1992. He is in my mind the leading scholar on the Lincoln County War, an accomplishment in itself since he lives in England and did most of his research from there augmented by occasional trips to the U.S.

So, imagine my surprise on the day before Thanksgiving of 1994, just weeks after Bantam published The Demise of Billy the Kid, when I went to the mailbox and found a letter from England with Mr. Nolan’s return address on it. Being a glass-half-empty kind of a fellow, I feared he was writing me to tell me I had plagiarized a sentence or something because I had used his works extensively to try to make the book as accurate as possible, even if it was fiction.

Mr. Nolan, though, was nothing but complimentary, calling Demise “a tour-de-force, a marvelous amalgam of just enough fact and exactly the right amount of fiction.” I was beaming and still am to this day a quarter of a century later that such an authoritative historian on the Lincoln County War took the time to find my address and send me such a glowing letter about my novelization of the facts. Little acts of support from fellow authors—and Mr. Nolan has written both nonfiction and fiction including several western novels—are among the most rewarding and enduring benefits of being a writer.